Projects, The Whispering of Ghosts

The Whispering of Ghosts 2018-2020

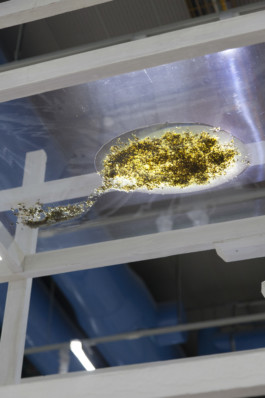

On the occasion of the 10th edition of Liverpool Biennial, Beautiful world, where are you? Mohamed Bourouissa has created a film and a community garden. The project is inspired by a garden created by a patient of the psychoanalyst and writer Frantz Fanon at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Blida, Algeria. Fanon proved that the failure of occupational therapy in Algeria was caused by the doctors’ incapacity to consider the patients’ societal background. His patient formed his approach of occupational therapy through gardening, and reflected the organisation of his mental space in the structure of his garden. Mohamed has learned the patient’s approach to botany, architecture and therapy, and created a similar garden with the local community, gardeners and artists. Some of the plants of this garden are chosen from an unfinished Algerian herbarium from the 1950s. With the community, Bourouissa has looked at the transformation of these plants in England, and selected the site and develop the garden. Drawing upon ‘resilience', a concept and term used in psychology, ecology and natural science, the garden is a space of resilience.

The whispering of ghosts, 2018, video color and sound, 13’21’’ © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP - Commissioned by Liverpool Biennal

Works :

Shown at :

• La Déconniatrie : Art, exil et psychiatrie autour de François Tosquelles, Les Abattoirs, Toulouse (FR), 2021-2022

• Le Déracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations, Z33-House for Contemporary Art Design and Architecture, Hasselt (BE), 2021

• The Space Between Classrooms, Swiss Institute Contemporary Art, New-York City (US), 2021

• Pas le temps pour les regrets, Prix Marcel Duchamp 2018, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (FR), 2018

• Beautiful world, where are you?, 10th Biennal of Liverpool, FACT, Liverpool (UK), 2018

Resilience Garden, 2018, outside installation for the 10th Liverpool Biennal, mixed media, variable sizes

Resilience Garden, 2018, outside installation for the 10th Liverpool Biennal, mixed media, variable sizes

Pas le temps pour les regrets, 2018, installation: wooden structure and video color and sound, variable sizes

Pas le temps pour les regrets, 2018, installation: wooden structure and video color and sound, variable sizes

The whispering of ghosts, 2021, installation: wooden structure and video color and sound, variable sizes

The whispering of ghosts, 2021, installation: wooden structure and video color and sound, variable sizes

La Déconniatrie : Art, exil et psychiatrie autour de François Tosquelles, Les Abattoirs, Toulouse (FR), 2021-2022 © les Abattoirs, Musée - Frac Occitanie Toulouse. Photographs : Damien Aspe

Exhibition views of Le Déracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations, Z33-House for Contemporary Art Design and Architecture, Hasselt (BE), 2021 © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP. Photographs: Selma Gurbuz

Exhibition views of Pas le temps pour les regrets, Prix Marcel Duchamp 2018, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (FR), 2018 © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP. Photographs: Hervé Véronèse

Exhibition views of Pas le temps pour les regrets, Prix Marcel Duchamp 2018, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (FR), 2018 © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP. Photographs: Hervé Véronèse

Exhibition views of Resilience Garden for the 10th Liverpool Biennal, 2018 © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP.

Exhibition views of Resilience Garden for the 10th Liverpool Biennal, 2018 © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP.

Bourouissa’s Method

Carlos Basualdo 2018

Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.

-“Hamlet,” William Shakespeare

As it is often the case in his work, what Mohamed Bourouissa ultimately offers us with his new installation “Pas le temps pour le regrets,” is just an image –an image that is both precise and poignant.The process by which it is produced is, nonetheless, complex.A wooden scaffold that stands for a section of the floor plan of a building contains a rotating screen that, like a tragic carousel, presents us with the contrasting faces of Bourlem Mohamed, an old time patience of the Blida Hospital in Joinville -the first psychiatric hospital in Algiers-, and that of the founder of the hospital, a French doctor, Antoine Porot, who worked there from 1938 until 1953. The Liverpool Biennial originally commissioned the film, entitled “Le murmur des fantômes.”As it is frequently the case in his work, Bourouissa presented in Liverpool an earlier version of the film along with an installation, “Resilience Garden,” an open garden in public space. It needs to be said that for Bourouissa, exhibitions have become deliberate tools for the development of his projects, so that several versions of a work are being presented in different venues through a certain period of time. In “Le murmur des fantômes,” Bourlem Mohamed, interviewed by Bourouissa recalls being tortured by the French colonial police, speaks about his garden in the hospital and his illness, questions Bourouissa about the artist leaving his homeland to work abroad, and helps him design a garden that will be subsequently built in Liverpool. This is a composite image, an arrangement of irreconcilable fragments, the fissures between them made even deeper by the episodic appearances of the inimitable voice of Franz Franon, heavy with a Caribbean accent, describing the psychological damage that domination inescapably inflicts to the colonial subject.

Since “Peripheriques,” and along the intense arch that take us from those early photographic images and through his celebrated videos “Temp Morts,” 2009 and “Légende,” 2010 to his ambitious multimedia installation “Horse Day” from 2015, Bourouissa has always been fundamentally concerned with the production of a complex and enigmatic image. This is an important fact to underline, especially because in Bourouissa’s work the process by which his projects come into being acquires such an evident protagonist role. There is a conspicuous tension between the process, always expansive and time consuming and such an important aspect of the display and reception of Bourouissa’s work, and the strange, magnetic power of the image that it is ultimately offered -an image that often remains with us, even against our will. Roland Barthes used the word “punctum” to refer to that miraculous articulation between parts and whole in which the absolutely singular stands out, beyond and above generalizations, as a cipher of an entire worldview. In that sense, Bourouissa’s method is to reveal the image as “punctum” of a certain specific and evolving situation.

Resilience, Bourouissa, says, is what his new work is concerned with. Looking at his early photographs one could say that resilience, the capacity to resist the most adverse conditions and to persevere along a certain path, is what his work has always been about. In the case of “Pas le temps pour le regrets” it is about Bourlen Mohamed’s resilience, written in indelible ink all over his body, expressed by his insistent work in a derelict garden at the hospital, an institution founded within the context of the French colonial project in Algeria, reflecting an oppressive value system. An institution that, in 1953, would employ a young doctor from Martinique, Frantz Fanon, who would soon introduce occupational therapy and music to treat its colonial subjects, the patients. Bourlen Mohamed’s work exists as a testimony of Fanon’s clinical reforms, the embodied echo of an emancipatory gesture.

But resilience is also the sign under which the staged compositions of “Peripheriques” were predicated, the quality that made Bourouissa’s “Horse Day” such a powerful symbol of the struggles and the victories of the African American community in West Philadelphia –and beyond. Resilience is a mark of agency. Bourouissa’s work focuses on situations that are always related to the emergence of a configuration of economical and political forces at specific moments in contemporary history, when certain subjects are threatened and their agency is under attack. Although explicitly critical of humanism in its Western, colonial version, Bourouissa’s work is always an attempt to restitute agency to those resilient subjects, to provide them with a sense of dignity.

Bourouissa attempts to do that by engaging as deeply as he is able to with the specific situation with which he has chosen to work. His position in this regard is not that of a disinterested viewer, a witness uninvolved with what he sees. Either already part of the situation that his work addresses -as was the case with “Periferiques,” that depicted a reality that was his own-, or a willful and fearless initiated -like in his work with the community of horse breeders in West Philadelphia-, the form of participation that Bourouissa choses for his projects is always that of an active engagement. Bourouissa’s engagement is the necessary tool that as an artist he requires for the production of form. In his work, the process of engagement results in the production of forms of staging. Bourouissa, in conversation, has acknowledged his intension to work with artistic forms that could be fundamentally inclusive. That might explain why the stage, being literal, like in “Horse Day,” or metaphoric, like the platform provided by the conversation and mutual agreement between the artist and a jailed prisoner in “Temps Morts,” appears so insistently in his work. This is, perhaps, the way in which his new installation at the Beaubourg needs to be understood, as a stage that encompasses the personal history of Bourlen Mohamed, the institutional history of the Blida Hospital, the intellectual history of Frantz Fanon, and more in general, the tragic history of the conflicted relation between France and its former colonies. The viewers are actors in that stage that both includes and questions them inasmuch as those histories are not external, but an intimate, although sometimes willfully forgotten or suppressed, part of their lives.

But at the same time, what Bourouissa stages, in this recent work as much as in the past, is an allegory, understood in the sense that Walter Benjamin referred to them when describing the German Baroque Drama; a collection of fragments that stands for the ruinous result of that long siege which is our recent history, the history of our times. Fanon’s voice, the skeletal armature of an institution of oppression, the endless loop of a disjointed and painful narrative, the weathered physiognomy of Bourlen Mohamed, all fragments, irredeemable, that engulf us in their pull toward a center of pure devastation. It is in that inaccessible center that the garden of resilience, nonetheless, continues to grow.